In his studio, Ye picked up a leather bulb pump and squeezed it constantly to blow away the fine dust on his vinyl records and record player. “I know I might seem fussy,” he laughed in embarrassment. “But the truth is, I am only fussy about music.”

Over the past 19 years, Ye has produced over 2,500 pieces of music and won many awards, including the Special Award for Best Musician at the 2009 China Gold Record Awards, the Chinese music industry’s top endorsement. Ye remains modest despite his many accolades, saying that all he’s really done in the past 19 years is play and promote Chinese music.

A project is born

“Every year, I spend a lot of time undertaking exchanges in foreign countries. One question I often hear is, ‘What is Chinese music?’ No one can come up with the perfect answer to such a complex question. China’s music is cultivated across its territory. It carries within it thousands of years of culture and history,” Ye said. Fifty-six ethnic groups, hundreds of musical instruments, and nearly a thousand kinds of opera constitute a huge and rich musical tapestry. “So, I decided to create a system to decode Chinese music from physical, ethnic, geographical and instrumental perspectives,” he added.

As part of this project, one major branch of Ye’s work is recording lesser-known or endangered Chinese traditional music with world-class equipment and technology. “So that centuries from now, future generations can still hear and enjoy it through both audio and video. This music is part of our cultural memory,” Ye said. “Cultures are vanishing faster than we can imagine, and when lifestyles change dramatically, traditional cultures evaporate. Take chanties and other work songs for example. If they are no longer needed in labor because of mechanization, their disappearance is almost instantaneous and inevitable.”

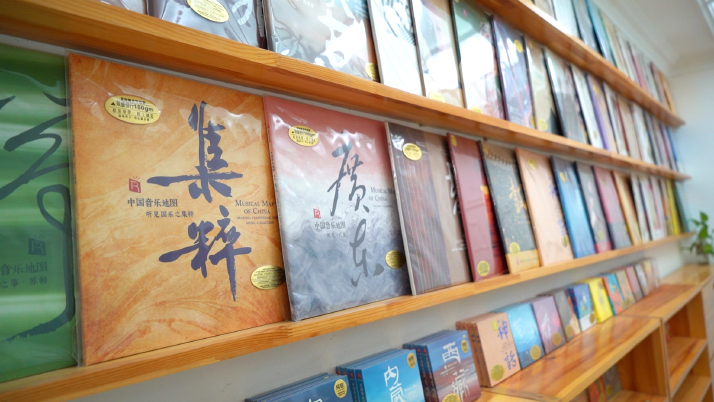

In 2019, as a chief producer, Ye officially launched the program Musical Map of China, which was not only subsidized by the National Art Fund but also listed as a key national publishing project during China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-25) period. “In the form of a map, I try to organize and express Chinese music piece by piece.” So far, Ye and his team have been to half of the provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities across the country to record folk music. The project has attracted the participation of approximately 580 people from nearly 40 ethnic groups, including inheritors of national-level intangible cultural heritage. So far, 1,056 pieces of music, played on more than 200 kinds of musical instrument, have been collected by the project. “We will continue to work on this project for at least the next 10 years, or even for the rest of my life,” Ye said.

When asked about the immense efforts such a grand project requires, Ye humbly joked, “If this project is a pearl necklace, those eminent singers, performers, composers, and sound engineers are the luminous beads, and I’m just the 2 yuan thread that strings them all together.”

A crescendo

“Old trees should grow new leaves” is this musician’s pet phrase, and Ye is acutely aware that simply recording traditional music is not enough to keep it alive. “Sometimes traditional things can seem distant from the present,” he noted. “The essence of traditional culture will not fade with time, but we need to uncover that essence and reassemble it to make it something modern, or something that can connect the past with the future.”

Ye took his cue from Turandot, the world-renowned Italian opera by Giacomo Puccini. “The story of Turandot is set in China, so Puccini employed massive Chinese elements in his composition. For instance, the appearance of the princess is accompanied by the Chinese folk song Mo Li Hua (Jasmine Flower),” Ye said. “This consonance made me realize the compatibility of Chinese and Western music and the possibility of mastering my own fusion, as long as I could find solid common ground.”

To find this common ground, Ye immerses himself in music and the cultures within it. “Music is like an ocean to me. A true lover of swimming will not be satisfied with the pool in front of them; they want to explore the ocean,” Ye said. “So I often work with people of diverse ethnicities and races to look for ways to integrate with them musically. I want to ‘make old trees grow new leaves’ through ocean-wide study.”

Ye shared one of his success stories of musical integration. On NetEase Cloud Music, China’s Spotify equivalent, a fan of Rhymoi Music commented, “When my colleague saw the Sichuan folk song Beaming With Joy at Sunrise on my playlist, he was side-eyeing me and mocking my taste in music. But when the melody flowed, he was astonished.” Ye adapted the song to be played in a blues style, finding harmony between the two genres. “When recording and producing the album, I found a similarity between the two genres—they both belong to people surviving tough times, who had no choice but to stay positive. This optimistic attitude chimes in with all of us, regardless nationality, race or language,” he said.

“Now, the world is ‘flat.’ Cultures of other countries can blend in with ours and generate new results. And music can fill the gaps between different nationalities, races and languages with emotions. We share emotions,” Ye added.

“We create music adhering to these aesthetic principles—picking out the temperaments of different music genres and amplifying them, based on their underlying commonalities, to produce a rich, three-dimensional form of Chinese music,” he concluded.

-The Daily Mail-Beijing review news exchange item