As part of its efforts to improve environmental governance, China is shifting its focus from controlling energy consumption to controlling carbon emissions. Over the past decade, the Central Government has set binding targets for provincial-level authorities on total energy consumption and energy intensity, or the amount of energy consumed per unit of GDP.

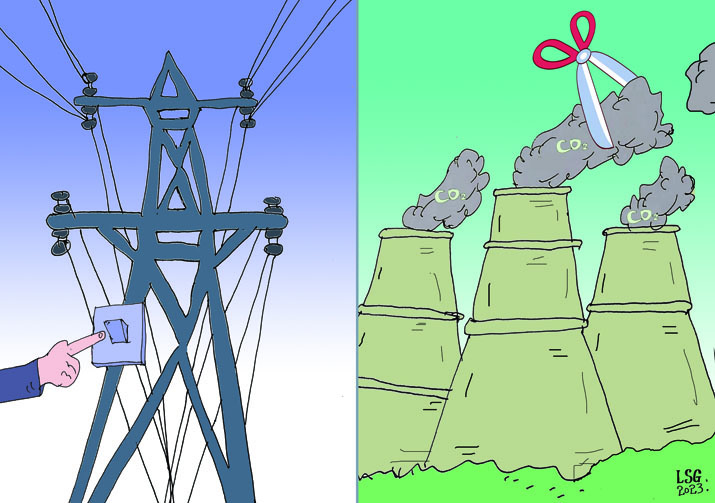

Since China first announced its goals in 2020 to peak carbon dioxide emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060, the flaws in this system have become apparent. For example, total energy consumption includes not only fossil fuels, but also non-fossil fuels such as nuclear and renewable energy.

Limiting the total amount of energy consumed may discourage the development and use of renewable energy, which in turn slows economic growth in areas rich in such energy resources. In addition, said consumption includes the use of energy as a raw material. Controls may leave reasonable demand in certain industries, such as petrochemicals, unmet. The energy control mechanism is therefore inconsistent with China’s goals of carbon peaking and neutrality.

Two years ago, the central authorities called for a transition to binding targets on total carbon dioxide emissions and carbon intensity, or carbon dioxide emissions per unit of GDP. In July, the Central Government reiterated in an official document the importance of building basic capacity to support the carbon control mechanism. According to statistics from the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, China’s carbon intensity in 2020 was 18.8 percent lower than in 2015 and 48.4 percent lower than in 2005, more than fulfilling the country’s pledge to the international community of a 40-45 percent reduction.

Over the past four decades or so, 80 percent of carbon emissions in China have come from fossil fuels. Energy use controls have, of course, helped reverse the rapid growth of carbon dioxide emissions. Carbon controls are more targeted as they limit emissions from both energy use and non-energy activities such as waste disposal and agricultural production, but do not limit the consumption of zero-emission renewable energy.

The introduction of binding targets on carbon intensity and total emissions will push China to better achieve its goals of emission reduction, energy security and restructuring, and faster development of renewable energy.

China has now entered a critical period of green development centered on carbon peaking and neutrality. The transition to carbon controls will require more innovation in emission reduction technologies, a faster energy transition, low-carbon economic growth, and a transformation of emission reduction systems.

To this end, it’s necessary to formulate effective top-level policies, while encouraging individual sectors and local governments to work out specific measures. Carbon accounting, a specific type of greenhouse gas accounting and a technique used to understand an organization’s carbon emissions, can be a viable measure to hold companies, individuals and governments at various levels accountable for their carbon emission activities.

It’s also important to make full use of market tools. Currently, China’s carbon market, which offers a limited range of trading products, is open to large emitters in the power generation industry only. Carbon markets are trading systems where carbon credits are bought and sold. Companies or individuals can use carbon markets to offset their emissions by purchasing carbon credits from entities that remove or reduce emissions.

More industries should be allowed to enter the carbon market so that the market can play a major role in accelerating the transition from controlling energy consumption to controlling carbon emissions. By shifting to the new policy, which covers a more extensive range of industries, China once again demonstrates its determination to go green. –The Daily Mail-Beijing Review news exchange item