We now face, on all fronts, a war not just against the living planet and the common good, but against material reality. Power in the United States will soon be shared between people who believe they will ascend to sit at the right hand of God, perhaps after a cleansing apocalypse; and people who believe their consciousness will be uploaded on to machines in a great Singularity. The Christian rapture and the tech rapture are essentially the same belief. Both are examples of “substance dualism”: the idea that the mind or soul can exist in a realm separate from the body.

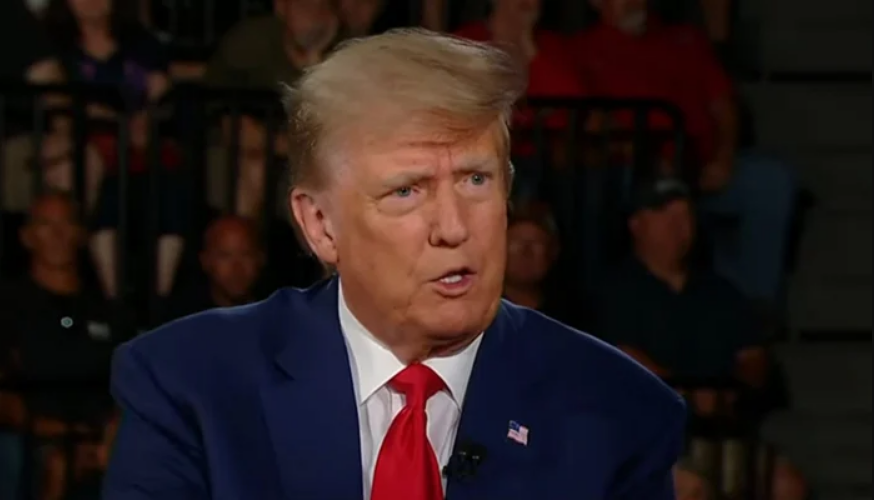

This idea often drives a desire to escape from the grubby immanence of life on Earth. Once the rapture is achieved, there will be no need for a living planet. But while it is easy to point to the counter-qualified, science-denying fanatics Donald Trump is appointing to high office, the war against reality is everywhere. You can see it in the British government’s carbon capture and storage scheme, a new fossil fuel project that will greatly raise emissions but is dressed up as a climate solution. And it informs every aspect of this week’s Cop29 climate talks in Azerbaijan.

Here, as everywhere, the living planet is forgotten while capital extends its frontiers. The one thing Cop29 has achieved so far – and it may well be the only thing – is an attempt to rush through new rules for carbon markets, enabling countries and businesses to trade carbon credits – which amount, in effect, to permission to carry on polluting. In theory, you could justify a role for such markets, if they were used only to counteract emissions that are otherwise impossible to reduce (each credit purchased is meant to represent a tonne of carbon dioxide that has been reduced or removed from the atmosphere). But they’re routinely used as a first resort: a substitute for decarbonisation at home. The living world has become a dump for policy failure.

Essential as ecological carbon stores are, trading them against fossil fuel emissions, which is how these markets operate, cannot possibly work.

The carbon that current ecosystems can absorb in one year is pitched against the burning of fossil carbon accumulated by ancient ecosystems over many years. Nowhere is this magical thinking more apparent than in soil carbon markets, a great new adventure for commodity traders selling both kinds of carbon market products: official “credits” and voluntary carbon offsets. Every form of wishful thinking, over-claiming and outright fraud that has blighted the carbon market so far is magnified when it comes to soil.

We should do all we can to protect and restore soil carbon. About 80% of the organic carbon on the land surface of the planet is held in soil. It’s essential for soil health. There should be strong rules and incentives for good soil management. But there is no realistic way in which carbon trading can help. Here are the reasons why. First, tradable increments of soil carbon are impossible to measure. Because soil depths can vary greatly even within one field, there is currently no accurate, affordable means of estimating soil volume. Nor do we have a good-enough test, across a field or a farm, for bulk density – the amount of soil packed into a given volume. So, even if you could produce a reliable measure of carbon per cubic metre of soil, if you don’t know how much soil you have, you can’t calculate the impact of any changes you make.

A reliable measure of soil carbon per cubic metre is also elusive, as carbon levels can fluctuate massively from one spot to the next. Repeated measurements from thousands of sites across a farm, necessary to show how carbon levels are changing, would be prohibitively expensive. Nor are simulation models, on which the whole market relies, an effective substitute for measurement. So much for the “verification” supposed to underpin this trade. Second, soil is a complex, biological system that seeks equilibrium. With the exception of peat, it reaches equilibrium at a carbon-to-nitrogen ratio of roughly 12:1. This means that if you want to raise soil carbon, in most cases you will also need to raise soil nitrogen. But whether nitrogen is applied in synthetic fertilisers or in animal manure, it’s a major source of greenhouse gas emissions, which could counteract any gains in soil carbon. It is also one of the most potent causes of water pollution.

Third, carbon levels in agricultural soils soon saturate. Some promoters of soil carbon credits create the impression that accumulation can continue indefinitely. It can’t. There’s a limit to how much a given soil can absorb. Fourth, any accumulation is reversible. Soil is a highly dynamic system: you cannot permanently lock carbon into it. Microbes constantly process carbon, sometimes stitching it into the soil, sometimes releasing it: this is an essential property of soil health. With rises in temperature, the carbon sequestration you’ve paid for can simply evaporate: there’s likely to be a massive outgassing of carbon from soils as a direct result of continued heating. Droughts can also hammer soil carbon.

Even under current market standards, in which science takes second place to money, you need to show that carbon storage will last for a minimum of 40 years. There is no way of guaranteeing that carbon accumulation in soil will last that long. But as a new paper in Nature argues: “A CO2 storage period of less than 1,000 years is insufficient for neutralising remaining fossil CO2 emissions.” The only form of organic carbon that might last this long – though only under certain conditions – is added biochar (fine-grained charcoal). But biochar is phenomenally expensive: the cheapest source I was able to find costs roughly 26 times as much as agricultural lime, which itself costs too much for many farmers. There’s a limited amount of material that can be turned into biochar. While making it, if you get the burn just slightly wrong, the methane, nitrous oxide and black carbon you produce will cancel any carbon savings. There is a kind of substance dualism at work here, too: a concept of soil and soil carbon entirely detached from their earthly realities. This bubble of delusion will burst. If I were a devious financier, I would short the stocks of companies selling these credits. All such approaches are substitutes for action, whose primary purpose is to enable governments to avoid conflict with powerful interests, especially the fossil fuel industry. At a moment of existential crisis, governments everywhere are retreating into a dreamworld, in which impossible contradictions are reconciled. You can send your legions to war with reality, but eventually we all lose.