Beijing: Why is the UFLPA unreasonable and where does the act prove inaccurate?

Peng Jun: First of all, the basic assumption of the UFLPA is wrong. The act assumes that almost all, if not all, Xinjiang entities use forced labor for their production and that the poverty alleviation programs are equated with forced labor. These presumptions are wide of the mark because they completely ignore the large number of contrary facts that are publicly available. Meanwhile, the UFLPA provides U.S. importers rather than Chinese exporters which are wrongly presumed to use forced labor with a channel to refute the allegations.

And when the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) does finally allow for the import to go through based on the terms of exceptions, it has to hand in a detailed report to the U.S. Congress. The overall process puts great pressure on the CBP and it will therefore be very cautious in giving permission.

In addition, requirements on supply chain traceability and compliance mean companies should not only prove they do not use forced labor, but also that the overall industrial chain, including multiple levels of upstream suppliers, does not either. Moreover, their control over suppliers doesn’t stretch beyond the contracts signed with the first level of suppliers. And if suppliers can cooperate, they, too, will need to trace their suppliers; the “running costs” will be extremely high.

What are the consequences of the UFLPA?

The UFLPA does not do anyone any favors. In other words, this decree will have an adverse impact both on Chinese and U.S. enterprises.

The act will directly impact the sales of Xinjiang enterprises. The UFLPA’s potential effects may prove similar to those of the CBP-issued Withhold Release Order against cotton products and tomato products produced in Xinjiang which came into force on January 13, 2021 in response to so-called “forced labor” concerns.

We have compared the exports of Xinjiang cotton products to the U.S. in the second half of 2020 and in the first half of 2021. The Xinjiang exports of 29 product categories, including cotton socks, cotton T-shirts and cotton bed sheets, to the U.S. decreased tremendously, with many exports reduced to zero; total exports decreased by 88 percent. We can infer that with the UFLPA in full effect, Xinjiang’s exports to the U.S. will decline rapidly and sharply, hugely affecting Xinjiang’s foreign trade.

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) will be “kicked out” of the U.S. supply chain. Large enterprises might be capable of undertaking and digesting the extremely high costs of supply chain tracing and compliance, but SMEs who fall short of subjective willingness and objective capacity to afford the costs will be excluded from the supply chain as a result.

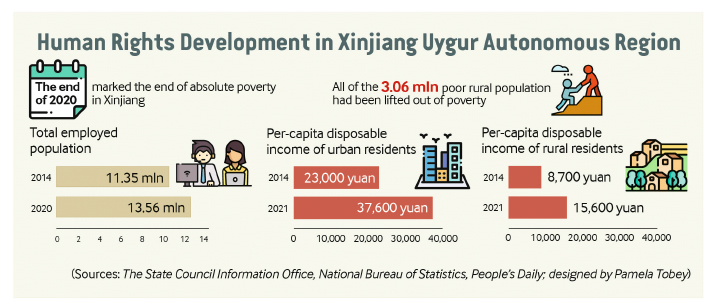

The exclusion of Xinjiang entities will seriously damage the region’s economy and lower the living standards of its residents.

For U.S. enterprises, the exclusion of SMEs will result in a supply reduction, in turn leading to an increase in prices of imported goods. If things continue this way, only a handful of large enterprises will come to monopolize the whole supply chain, further driving up prices and intensifying inflation. This will distress the efficiency and innovation capacity of participants across the supply chain. Interfering with a normal and dynamic supply chain through incorrect assumptions and non-economic means will only distort, even destroy, healthy competition.

How do you suggest enterprises respond to the UFLPA?

How do you suggest enterprises respond to the UFLPA?

Enterprises have to recognize the act’s underlying political tone. While political matters are for governments to solve, enterprises should focus on coping with economic matters. In other words, no matter the outcome, enterprises should adopt economic and legal measures to maintain their market shares and exports to the U.S.—despite complications and costs.

One pragmatic approach for the enterprises would be to create a “dual circulation” supply chain: one for U.S. business and another for non-U.S. business. Suppliers on the U.S. side should then forge closer cooperative ties to provide the required documents. In reality, a number of enterprises have already been doing this.

Prosecuting the UFLPA through international platforms may be another option. Non-discrimination is a key principle of the World Trade Organization (WTO). It stipulates a country should not discriminate between its trading partners and between its own and foreign products, services or nationals. Yet the UFLPA specifically targets Xinjiang, evidently going against this basic principle.

Transparency is another critical WTO member obligation, defined as “the degree to which trade policies and practices, and the process by which they are established, are open and predictable.” The UFLPA’s provisions for enforcement oppose its purpose of protecting the rights of Xinjiang residents and workers, and it can’t provide enterprises with either transparency or predictability.

–The Daily Mail-Beijing review news exchange item