The 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) begun in Beijing on Sunday. The event, which happens every five years and usually lasts for several days, includes announcements, resolutions, and eventually the revelation of the new Standing Committee, the small group of core leaders within the 25-person Politburo. Traditionally, the Party Congress would also see the replacement of the top leadership: CCP General Secretary and Chinese President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang.

But Xi’s rule has been anything but normal. Not only did the 19th Party Congress in 2017 not reveal the next generation of leadership, but Xi also changed the rules the next year to allow himself to effectively rule for life—while picking off potential rivals through political purges. Although the premier has always been far less powerful than the party chief, the eclipse of Li has been dramatic, despite a slight return to the spotlight as the economy tottered this year.

China has seen just two peaceful transfers of power from one generation of leadership to the next under the current system: from Jiang Zemin to Hu Jintao and from Hu to Xi. (Deng Xiaoping’s more unusual, gradual handoff of power to Jiang and others might also count.) Nor did the system work exactly as planned: In the early years of his rule, Hu struggled against Jiang’s influence until a compromise was likely worked out behind the scenes.

The timing of China’s Party Congresses offers a glimpse into the instability of China’s recent political past.

The 1st Party Congress was almost exactly a century ago—back when the CCP was a revolutionary movement, not a government—but the every-five-years timing has only been in place since 1977, as the party sought to establish a post-Mao Zedong sense of order.

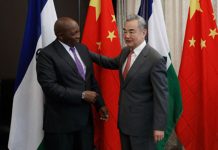

The orderly leadership succession was supposed to signal that China’s was a more reliable form of authoritarianism, one that the world could do business with. This was matched by so-called collective leadership—the idea that the powerful party chief was still to some degree a first among equals and that the rest of the leadership as well as retired elders would prevent a new Mao from emerging.

Xi’s rise has shattered all that. There is no question of who is in charge, and it would be very unlikely for that to change after the 20th Party Congress.

For the moment, it’s Xi forever, with his image plastered all over China’s daily propaganda. The question is who falls beneath him and whether they have any real power to push their own agendas, especially when it comes to fixing an increasingly shaky economy. –Agencies