A long-established gemstone shop run by a Pakistani family is the largest and most reputed one in Tashikuergan (Taxkorgan) Tajik Autonomous County. Amin Karim, the current owner of the shop, took over from his father and uncle more than a decade ago. Over the years, his family has witnessed the China-Pakistan border trade burgeoning.

That is where the documentary A Place to Call Home starts. It tells the stories of expats from countries as diverse as Pakistan, the UK, Cuba and Belgium who have settled down in Xinjiang, merging into local life. For Xu Xiaojuan, producer of the documentary, the stories are not about how foreigners view Xinjiang, but how a place where they have found peace of heart became their second home.

Xu is a professor at the Communication University of Zhejiang in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province. The documentary was inspired by her observations of Xinjiang, where she was born, went to school and got married.

“Over the past more than 20 years, I have gradually come to realize that what the narrative about Xinjiang truly lacks is daily life stories—the real and subtle perspectives,” she told Xinjiang Today. “When I see more and more people from different countries doing business, teaching and settling down in Xinjiang, I feel the concept of ‘home’ is being rewritten here.”

Real people, real lives

The documentary traces Karim expanding his family business from gemstones to mango juice from Pakistan.

British student Luke Johnston, who came to pursue his doctorate at Shanghai Jiao Tong University in Shanghai, now teaches in Xinjiang and has embraced the local culture.

Cuban coach Luisbey Sánchez trains boxers with passion. British travel vlogger Luka Gradzeviciute, married to a local, shares Xinjiang’s wonders with the world. Belgian entrepreneur Decombel Danny Camiel’s fertilizers help local farmers improve the soil, and he has become a permanent resident in Xinjiang.

For Xu, their commonality lies not in their identity as expats, but in their choice to live in Xinjiang.

Since the expats were interviewed and filmed many times before, the documentary team planned to do something different. “We decided not to have a story plot but just record everything that happens,” Xu said. “We also avoid preaching, instead presenting Xinjiang through real-life stories.”

The documentary shows Karim’s hesitation during business negotiations and Sánchez’s frustration when Dina, a 19-year-old female Kazak boxer he trained, loses a match. It also shows how Gradzeviciute tries to get close to his Chinese family, giving rise to embarrassing moments at times but heart-warming too.

“What moved me most is how the expats merged into the life in Xinjiang. Their action speaks louder than any words,” Xu said.

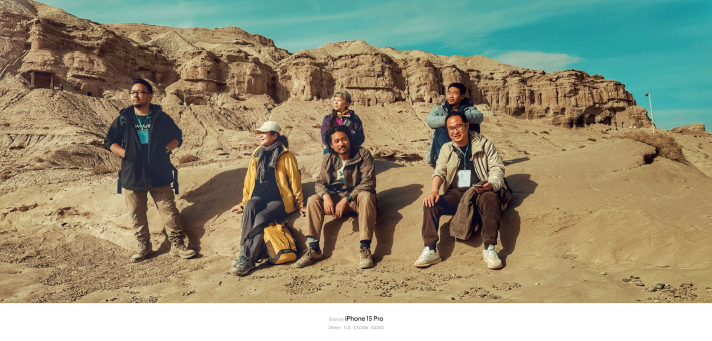

Ju Xiaotian, one of the directors of the documentary, joined the project out of curiosity about Xinjiang.”The stories are about mutual integration. They are not just adapting to Xinjiang, but experiencing mutual acceptance and influences during interaction with local people,” Ju said.

According to Xu, the team chose not to refute the existing narratives about Xinjiang, or create new narratives. They did what is basic in documentary filmmaking—recording reality. They recorded Xinjiang’s landscapes, culture and expats from different backgrounds to showcase its diversity.

“Audiences can empathize with the emotions and experiences of the figures filmed. We do not define Xinjiang, but only record it through our lens. Reality itself is powerful enough,” she said.

No smooth journey

The filming was not a smooth journey. Since most of the team members were not locals, they faced language barriers at first. Later a photographer skilled in multilingual communication resolved this issue.

Even slight changes in the weather could completely alter the lighting and emotions of a scene, and the team learned to embrace uncertainty.

According to Ju, they focused on micro perspectives to showcase individuals’ life and avoid stereotypes.

Yin Liqun, another director, said another challenging part was how to interact with the interviewees and gain their trust in a short time so that they were willing to share their lives. But the team’s sincerity persuaded them.

Before filming the documentary, Yin had never been to Xinjiang. His understanding of the autonomous region mostly came from the Internet or movies, and he thought of it as an exotic place. “After I went to Xinjiang, I found that it is not largely different from what I expected,” he said. “We hope we have portrayed a modern, open, inclusive and vibrant Xinjiang through showing how the protagonists interacted with the local people. The best way to combat stigmatization is to showcase real-life details.”

A second home

For the filmed expats, Xinjiang has become their second home. “Almost every one of them told me that they never felt like outsiders in Xinjiang,” Ju said.

The documentary shows Camiel on a farm in Xinjiang. He sits in a chair in the open cattle shed with a glass of wine, talking with his friends, the local farmers.

“When local farmers came to chat with him or ask about fertilizers, I felt he was not an outsider but a local. He has adapted to local life, and found joy in seizing business opportunities and helping others,” Gan Xin, another director, said.

For Ju, the most moving moment occurred in June, when they were filming the decisive qualifying match in which Dina took part. It was her last chance to make it to the final phase of the 15th National Games in November. Just a few months earlier, they had witnessed her lose a match, which left everyone in low spirits. In May, they filmed Dina during her training in Xinjiang, witnessing the arduous efforts she made for a comeback.

“As Dina stepped into the ring that day, I leaned on the railing, watching her. I realized my hands were trembling with nervousness. When she was announced the winner, I rushed to hug her,” Ju said.

Through the expats’ narratives, the audience can also see the transformation of Xinjiang. Karim’s uncle first visited China in November 1991. At that time, he said, they couldn’t find any restaurant open in Tashikuergan after dark, and the whole county had only two hotels. “The changes from 1993 to now are earth-shaking,” he added.

Many of the expats too have been introducing Xinjiang to the outside world through their lens. Johnston, now an English teacher in a middle school in Urumqi, has filmed his daily life in Xinjiang and posted the videos. They went viral on the Internet, gaining him thousands of followers.

“Many people have messaged me saying that I’ve inspired them to come to China and to Xinjiang. I think this is a good way for people to see the real side of it,” he says in the documentary.

With him, Ju visited a data center in Karamay in northwest Xinjiang that uses ultra-low-carbon liquid cooling technology. It made her understand more about the autonomous region. “I was surprised by the technological and innovative development in Xinjiang, just as he was,” she said.

A vibrant land

The most important change in Xinjiang over the years is the growing sense of happiness with life. The development of Xinjiang can now be seen on social media platforms as more and more young locals are filming their daily lives.

“Next, we hope to focus on the younger generations to show a modern Xinjiang, which is the real image of the region today,” Mai Kefeng, another director, told Xinjiang Today.

“Documentaries may not resolve differences, but could foster trust and recognition through real stories. I will continue to focus on daily life and cultural fusion to tell Xinjiang stories to global audiences,” Xu said.

The documentary ends with the lines: “Love crosses mountains and seas. The heart finds its way across all distance. Home, the anchor of every soul, is wherever one’s heart feels at peace.”

Home is where the heart is, and love and understanding cross all borders. –The Daily Mail-Beijing Review news exchange item