As both a lawyer and a mother of an infant, Wei Meng read the news with keen attention. The amendment to China’s Food Safety Law, which was passed in September and took effect on December 1, felt personal.

The new rules zero in on two key areas: tightening supervision of liquid infant formula and creating a licensing system for transporting bulk liquid foods by road. For Wei the mother, the first part was an immediate relief. Regarding the ready-to-drink formula her baby sometimes relies on, the law now explicitly bans its production through sub-packaging and requires strict product registration, to make sure the product follows a verified recipe and standard. Sub-packaging is the practice of repacking a larger, bulk quantities of a product into smaller, more convenient or more marketable units. The new rule prevents product quality being compromised during the sub-packaging process, building a legal shield around the product her child consumes.

For Wei the lawyer, the amendment didn’t just state a goal, but also engineered a solution. By instituting a mandatory licensing system for the bulk transport of liquid foodstuffs and clearly delineating the responsibilities of consignors, carriers and receivers, the law effectively closed a significant regulatory loophole. Its stringent prohibition on falsifying transport or cleaning records, reinforced by substantial penalties, demonstrated the legislators’ astute understanding of potential systemic vulnerabilities. In her view, this amendment—one of several since the law’s inception in 2009—signaled a legal framework capable of learning from experience and dynamically adapting to emerging risks.

“As both the primary guardian of my family’s health and a legal professional, the latest amendment to the Food Safety Law demonstrates how a well-crafted law can align personal wellbeing with public order,” Wei told Beijing Review. “It’s a powerful example of the rule of law functioning not as an abstract concept, but as a tangible guardian of society’s most fundamental unit: the family.”

The recent amendment to the Food Safety Law along with the introduction and amendment of other laws, are vivid examples of how the rule of law functions in today’s China—not as a static set of rules, but as a living system that responds to new challenges.

“The people-centered philosophy of law-based governance is being translated into reality through a series of tangible measures in aspects of legislative, law enforcement and judicial practices,” Yuan Gang, Vice Dean of the School of Law at China University of Political Science and Law, told Beijing Review.

Law-based governance

The concept of the rule of law is deeply rooted in China’s long history of governance. From the ancient legalist principle of “governing the state according to law” to the Confucian emphasis on order and righteousness, China has long recognized that clear, stable rules are essential to social harmony and state stability.

In contemporary China, the rule of law has evolved into a cornerstone of socialist modernization. It is a natural progression of China’s own governance traditions—now integrated with Marxist legal theory and adapted to national conditions. The Constitution of the People’s Republic of China establishes that the country shall practice law-based governance and build a socialist state under the rule of law; all state organs and armed forces, all political parties and social organizations and all enterprises and public institutions must abide by the Constitution and the law.

Since the launch of reform and opening up in the late 1970s, China has systematically built a legal system that covers all critical aspects of economic and social life, from property rights and contract enforcement to environmental protection and consumer safety.

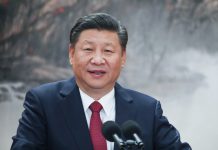

China’s rule-of-law process entered a new chapter in 2020, when the Communist Party of China (CPC) convened its first-ever Central Conference on Law-Based Governance, formally establishing Xi Jinping Thought on the Rule of Law as the guiding philosophy in this field. This was a historic milestone in achieving the long-term goal of building a socialist country under the rule of law.

Since the 18th CPC National Congress convened in 2012, Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the CPC Central Committee, Chinese President and Chairman of the Central Military Commission, has put forward a series of new concepts, ideas and strategies that have shaped China’s approach to law-based governance.

He gives answers to key questions such as why law-based governance in all respects should be pursued in the new era and how to achieve it, offering fundamental guidance for the steady and long-term advancement of law-based governance in China.

Under his guidance, a series of national plans, such as the plan to build the rule of law in China (2020-25) and guidelines for building a law-based government and law-based society, have provided a blueprint for advancing law-based governance.

In October, the Fourth Plenary Session of the 20th CPC Central Committee put forward its recommendations for formulating the 15th Five-Year Plan (2026-30). The key document highlights the significant role of the rule of law in China’s modernization endeavors and the realization of national rejuvenation, calling for stronger mechanisms for resolving administrative disputes and accelerating the development of its legal system and capabilities relating to foreign affairs.

In his recent instructions on comprehensively advancing the rule of law, Xi emphasized that China must fully advance sound legislation, strict law enforcement, impartial administration of justice and observance of the law by all, and place all aspects of state governance under the rule of law in order to provide a strong legal guarantee for building a strong country and advance national rejuvenation on all fronts through Chinese modernization.

Xi’s instructions were conveyed at the Central Conference on Law-Based Governance in Beijing from November 17 to 18. He also highlighted the necessity of safeguarding and promoting social fairness and justice, and comprehensively advancing rule of law in all aspects of the country’s work.

Principles to practice

According to Yuan, the concept of the rule of law is evolving from abstract principle into lived reality across China, guided by a governance philosophy that places people’s needs at its core. This shift is reflected not only in the refinement of laws but in their tangible implementation—whether in safeguarding vulnerable groups, innovating administrative enforcement, advancing judicial fairness or fostering a culture of legality in everyday life.

A notable example can be found in recent legislation. A law on building a barrier-free living environment, which took effect on September 1, 2023, underscores the commitment to improving the daily lives of people with disabilities and the elderly. The law also extends its protections to other groups with accessibility needs. It mandates that newly built, reconstructed or expanded residential buildings, public facilities, transportation infrastructure and urban and rural roads must comply with barrier-free construction standards.

Official statistics indicate that China is home to more than 85 million people with disabilities. This reality makes the implementation of such legislation not merely a matter of legal compliance, but a vital step toward social inclusion and equitable living.

On the legislative front, at a September 12 press conference in Beijing, Shen Chunyao, Director of the National People’s Congress (NPC) Standing Committee’s Legislative Affairs Commission, highlighted further progress on advancing the socialist rule of law with Chinese characteristics during the 14th Five-Year Plan period (2021-25). Since 2021, the NPC and its Standing Committee have revised 63 existing laws, passed 35 decisions on legal and major issues, and issued one legislative interpretation.

China currently has 306 laws in force, along with more than 600 administrative and supervisory regulations, and over 14,000 local regulations, Shen noted.

In the field of law enforcement, China has been advancing a paradigm shift toward more efficient and people-centered regulatory practices, with reforms aimed at standardizing administrative procedures and enhancing their responsiveness to public needs. Key initiatives include the “comprehensive single-inspection” model in the field of market regulation, which consolidates multiple regulatory checks into one coordinated visit to reduce redundancies and minimize disruptions to businesses; the “flexible enforcement list,” which exempts minor or first-time violations from penalties to emphasize guidance over punishment; and the introduction of unified templates used by administrative agencies to ensure lawful, consistent and traceable procedures, thereby enhancing efficiency and transparency.

“A tangible example of this people-centered approach can be observed if a driver enters an unfamiliar area and fails to follow the planned traffic route or parks improperly. They will promptly receive a text message reminder instead of an immediate fine or penalty notice,” Yuan further explained.

China has also established a comprehensive legal system relating to foreign affairs. According to a report introduced in May by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Institute of International Law, as of December 25, 2024, China had 54 laws specifically designed to address foreign affairs, and more than 150 others contain provisions involving foreign affairs.

To enhance its capacity of legal services in foreign affairs, China has actively deepened international legal exchanges and cooperation. At a press conference held on September 8 in Beijing focused on promoting socialist rule of law and judicial administration and serving high-quality development during the 14th Five-Year Plan period, Minister of Justice He Rong highlighted concrete steps in this area. She noted that China has signed 91 treaties on mutual legal assistance and 19 agreements on the transfer of sentenced persons, while handling over 16,000 international judicial assistance cases.

Future prospects

China’s efforts to build a people-centered rule of law system have achieved marked progress, yet practical challenges remain. Yuan notes that in legislation, certain laws addressing public welfare—such as elderly care services and public health emergency response—remain underdeveloped or overly general, limiting their ability to meet specific public needs.

In enforcement, disparities persist across regions and sectors, with some remote areas lacking sufficient capacity and occasionally applying rigid or inconsistent penalties, undermining fairness and predictability.

In the judicial domain, courts continue to face high caseloads with limited staff, resulting in extended trial periods in some cases, and measures to improve legal accessibility at the local level need further enhancement in reach and convenience.

Moreover, public legal awareness varies across urban and rural communities, and trust in modern dispute resolution mechanisms remains underdeveloped, posing ongoing challenges to fostering a society grounded in the rule of law.

Looking ahead, Yuan emphasized that efforts will focus on creating a modern, accessible public legal service system for all—urban and rural alike—through better resource allocation, standardized procedures and expanded digital platforms. “This will help ensure equal access to legal support, enhance public trust and deepen the people-oriented nature of the rule of law,” he concluded. –The Daily Mail-Beijing Review news exchange item