Technological advances are reshaping the world every day, from the era of the steam engine to the current focus on artificial intelligence (AI). These changes are not just technical, they also transform our economic structures, lifestyles and even cultural values.

While the West has long stood at the forefront of these seismic shifts, China’s burgeoning capabilities in science and technology are capturing global attention. The nation’s pace of innovation is not merely keeping up but accelerating, fueled by a reservoir of both experience and critical reflection.

It’s important to consider the broader implications of these technological shifts. We must examine whether technological innovations primarily serve the interests of individual countries or whether they can also advance global wellbeing? Are these innovations inherently competitive, or is there room for mutually beneficial advancements? And, perhaps most crucially, do they facilitate or hinder global economic integration?`

Cognition and pan-securitization

Over the past few centuries, the Western world has led the charge in major technological revolutions, including the steam engine, electricity and the information revolution. This dominance has fostered a widespread acknowledgment of Western technological innovations. Many in the West consider these achievements to be almost regional privileges. When non-Western countries, such as China, make significant technological strides that can benefit the world at large, they often encounter not recognition but suppression. This reaction fosters new conflicts within global technological innovation.

A primary conflict in today’s global tech competition stems from some nations framing technological advances through ideological or values disputes. For instance, China’s significant advancements in the electric vehicle industry, which could be seen as enhancing global production capacity, are instead criticized by some as creating “overcapacity.”

Globally, non-traditional security challenges within science and technology frequently generate negative impacts on innovative developments, a phenomenon exacerbated by the trends of “pan-securitization” and “politicization.” Some nations have expanded the concept of “security” beyond traditional bounds, encompassing sectors like semiconductors, quantum technologies and digital spaces.

This expansion has led to restrictive measures on tech innovation, market access and supply chains.

Even breakthroughs in Chinese technology, such as 5G or 6G infrastructure, are scrutinized under a political lens, needing to align with notions of “political correctness.” American economist Jeffrey Sachs, for one, in 2018 argued that the U.S. Government’s unilateral “America First” policy not only undermines international norms but also risks transforming the U.S. from a post-World War II leader into a “rogue nation” of the 21st century.

Following the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine conflict in early 2022, the global landscape has shifted dramatically, with Ukraine enduring the direct impact and Europe facing multifaceted losses.

Major European economies have seen downturns; industrial and supply chains are increasingly realigning toward the U.S.; and the euro’s role as a global trade settlement currency has plummeted.

The tech divide

The post-World War II industrial chain, supply chain connections and the pattern of global technological innovation cooperation have all been disrupted.

Driven by zero-sum thinking and a Cold War mentality, some countries have employed tactics like “decoupling,” “small yard and high fence,” and “de-risking,” using these as pretexts to sever technology cooperation that was once widely integrated within global industrial chains.

Leading enterprises and industries from countries at the forefront of innovation—such as France’s Alstom (a key player in the railway and transport industries), China’s Huawei (a tech titan), Japan’s automotive and semiconductor industries, Germany’s automotive industry—have all faced constraints and suppression under the U.S.’ long-arm jurisdiction.

During former U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration, technology became a central arena of strategic competition with China. The administration initiated the “China Initiative” conducting extensive investigations into Chinese scientists living in the U.S. and placing numerous Chinese enterprises on an “entity list” to hinder the exchange of knowledge between the two nations.

The current Joe Biden administration has continued this competitive stance, integrating zero-sum perspectives into tech competition and aligning allies against China.

Initiatives like the “U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council” and the “Chip 4 Alliance” aim to reduce dependence on Chinese sci-tech systems and supply chains. Policies like the CHIPS Act and Inflation Reduction Act have encouraged companies like TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.) and Nvidia to set up operations in the U.S., bolstering American semiconductor research and development.

AI, emblematic of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, represents a fusion of technology and human activity, altering traditional methods of human cognition. The rapid development of AI presents significant advancements but also introduces complex ethical concerns. Its capabilities to understand and predict user needs more accurately than traditional Internet or social media platforms—combined with technologies like deepfake—can amplify control and misinformation, fostering severe “information cocoons” and “consciousness manipulation.” In military applications, if AI development is not carefully managed, autonomous decision-making weapon systems could result in misuse, as seen with drone technologies in the Russia-Ukraine and Palestinian-Israeli conflicts. McKinsey & Co., an American multinational consulting firm, in 2018 predicted that by 2030, advancements in AI and other technologies will necessitate the reemployment of approximately 375 million workers worldwide—or roughly 14 percent of the global workforce.

As technological civilization moves forward, human civilization appears to regress.

While the United Nations has made some progress in fostering consensus among nations on security risks and cooperation, critical issues linger. Questions about creating rules for global tech cooperation, especially in frontier technology, original technology and basic theoretical research, remain unresolved. How can technology truly serve all of humanity, rather than entrenching the technological dominance of a few? Is it justified to use one country’s laws to sanction others, and are practices like long-arm jurisdiction reasonable? These pressing issues within the realm of global governance require attention.

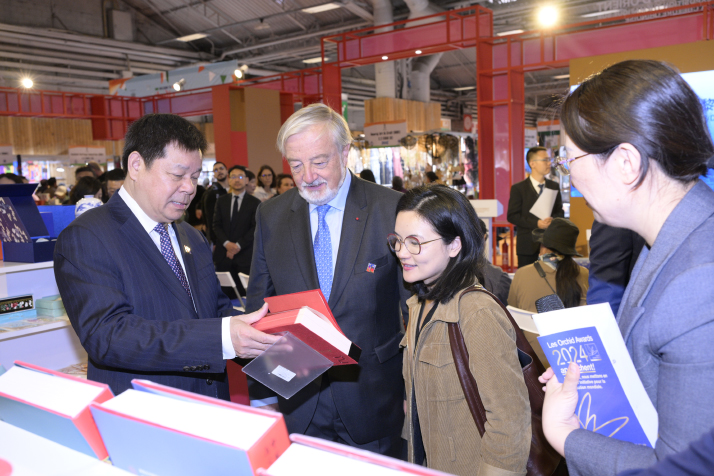

Sino-French opportunities

As two influential nations, China and France have unique opportunities to shape global governance. Their shared expertise in technological innovation can lead to foundational rules and standards that benefit not just their countries but the world at large. By actively participating in forums like the UN and the Group of 20 (the main forum for international economic cooperation made up of 19 countries and two regional bodies: the African Union and the European Union), they can ensure their perspectives help guide international policymaking.

Deepening scientific and technological ties between the two nations also promises significant benefits. Joint laboratories, for instance, could merge the strengths of both, spurring innovations that address urgent global challenges.

In industry and supply chain management, there’s a clear opportunity to build on existing relationships. French companies are well-established in China, contributing to local economies and creating integrated industry networks. A similar approach could be mirrored by Chinese companies in France, fostering balanced growth and cooperation.

Agriculture is another area ready for deeper cooperation. Both countries are leaders in agricultural technology and management, and by sharing knowledge and innovations, they can lift productivity and market integration.

Additionally, cultural and educational exchanges could be revitalized. Encouraging more European students, particularly from France, to study and experience life in China could bridge understanding and strengthen bilateral relations.

These collaborative efforts could redefine the partnership between China and France, paving the way for a more interconnected and prosperous future. –The Daily Mail-People’s Daily news exchange item