As the mercury rises in Turpan City, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in northwest China, social media posts paint a picture of a city simmering under the unyielding gaze of the sun.

Of the 140,000 posts with the hashtag “Turpan” on Xiaohongshu, a lifestyle and e-commerce platform wildly popular among China’s younger generations, many scream and echo “It’s so hot out here, I can’t take it anymore!” Quick disclaimer: Many of these snippets are related to sand therapy at the city’s Flaming Mountain, a 500-meter-tall red sandstone ridge. We’ll get back to that.

Turpan—or as the locals call it, “Fire City,” is the hottest spot in all of the Middle Kingdom and stands as a scorching testament to human resilience.

This place thrives on extremes. During the day, the sun is merciless, blasting the earth; yet nightfall brings some cool relief to the desert. In this stark realm of heat, lush vineyards sprawl defiantly at the feet of barren peaks, crafting a social media-worthy contrast. Life here ticks to the rhythm of grapes slowly morphing into raisins—a process measured, methodical and richly rewarding in its own sun-drenched way.

While these descriptions might conjure up images of a remote and rustic outpost, Turpan also pulses with trends that are both blisteringly hot and incredibly hip among Chinese urban youth.

Nighttime whispers

It’s early July, and this author begins her Turpan diary under the serene and cool(er) cloak of night, with a tale woven from the Jiaohe Ruins, an ancient city dug out from the yellow desert silt located some 10 km from the city.

Built around the second century B.C., Jiaohe, strategically positioned between two rivers, was a brilliant feat of ancient military architecture, safeguarding its inhabitants through dusty millennia. Meandering through the remnants, travelers will be transported to an era when the city thrummed as a vital heart along the ancient Silk Road—alive with the babble of foreign tongues and the heady aromas of spices from distant lands.

According to local legends, the murmuring of Jiaohe’s ancient residents can still be heard in the wind late at night, infusing the UNESCO site with a mystical aura that sends shivers down the spine of the modern visitor.

The sight of the ancient Jiaohe Ruins juxtaposed against the distant lights of urban Turpan makes for the picture-perfect daka spot—and your tour guide will not fail to mention this.

Many travel destinations, the Jiaohe Ruins included, have created full-fledged daka platforms offering the best angles to get travel photos. Daka (literally “punching a card”) means taking one’s photo at a hot destination and then show it off on social media. Daka tourism has become a hardcore industry over the past two to three years.

Nighttime flashes aside, it’s during the daytime that Turpan really turns up the trending heat…

The sands of time

Younger generations are increasingly infusing their beauty and wellness routines with elements and practices that date back to the imperial days (before 1912), and that includes a zest of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM).

This trend reflects a growing interest in holistic and natural health practices, which are seen as complementary to modern medicine and beauty treatments, according to a report on what’s driving wellness in China, released by Jing Daily, your go-to online portal for anything and everything regarding the business of luxury in China, in July.

TCM offers a range of practices from herbal treatments to acupuncture, which are being applied to modern lifestyles. For example, herbs and natural ingredients used in TCM are increasingly found in skincare products targeting everything from acne to signs of aging.

In what can be called a cultural reawakening, urban youth are also bringing back techniques such as sunbathing the back and guasha, scraping the skin with jade or plastic tools to improve blood flow, as part of modern wellness.

Chinese social media this summer is also ablaze with posts of users getting baked by the sun and soothed by the sand—in Turpan. We’re talking “sand therapy” (shaliao in Chinese).

Hashtag “sand therapy” had raked in 440 million posts on Douyin and “Turpan sand therapy” had garnered 8.8 million snippets as of July 24.

This age-old remedy is far more than simple sunbathing; it’s a dance of elements where heat meets health in the most dramatic of settings.

Imagine this: bodies half-buried in scorching sands, the air quivering above at over 40 degrees Celsius. Onlookers might puzzle over the sight, questioning the wisdom of baking in such extreme heat. Yet, what unfolds in these grains is a sophisticated symphony of natural therapy. The sand, supercharged by the fierce sun, acts like an open-air sauna, its intense heat believed to chase away the dampness that TCM links to ailments like rheumatoid arthritis and cervical spondylosis, according to a related article on ChinaSkinny, a website covering views, news and trends from China.

And the sands of Turpan, declared an “open-air sauna,” are not just hot; they’re healing. Rich in trace elements and basked in potent infrared radiation, these sands are said to boost cellular energy absorption and kick-start metabolism, while their relatively mild ultraviolet rays keep sunburn at bay.

This unique method, perfected by the people from the local Uygur ethnic group, has captured the fascination of Chinese health enthusiasts. As a cornerstone of cultural tourism in Turpan, sand therapy annually attracts over 300,000 visitors, each drawn to the promise of ancient wisdom cradled in the warm sands of time, the article on ChinaSkinny continued.

Thirsty yet?

Quenching the thirst

This author opted not to be half-buried in the searing sand. She instead moved on to her next stop to see where else young tourists to the area are quenching their social media and travel thirst. The answer turned out to be a photogenic gem that proved the perfect contrast to the earlier flaming fad: the ancient Karez water system.

An engineering marvel less celebrated but as vital as the veins in a body, the system is a network of underground channels, bringing glacier meltwater from the mountains to the once thirsty mouths of Xinjiang’s desert towns. This form of complex artery system, invisible beneath Earth’s surface, stretches over thousands of km. Crafted ingeniously some 2,000 years ago to avoid the brutal evaporation of the desert sun, like Turpan itself, these tunnels are a testament to human ingenuity and resilience.

The technology was possibly brought to Xinjiang from the Persian Empire by travelers on the Silk Road and then adapted to local conditions.

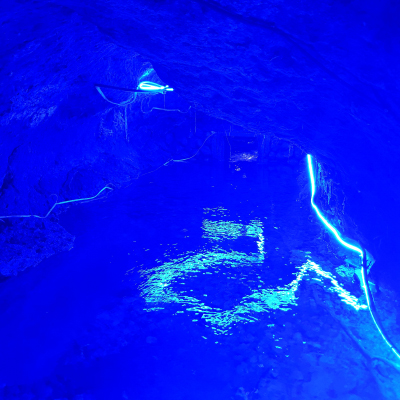

Today, you can “dive” into the ancient tunnel network in Turpan, going deep underground to observe the life-giving essence—that is water still calmly running through the longstanding tunnels. You will see many an explorer striking a pose in the tunnels now illuminated by neon blue lighting. Click, click, click, flash, flash, flash—all around.

Nevertheless, this stop oozed a sense of calm and quiet… Another thirst many Chinese urban youth have been seeking to quench in recent years.

The Buddhist beat

No pictures allowed at our final destination! Or, at least, not inside.

Tucked away behind the Flaming Mountain, the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves, dating from the fifth to the 14th centuries, stand as a monument to a time when spirituality and artistry flourished under the watchful eyes of different civilizations.

As you approach these sacred hollows, the walls come alive with the tales of 1,000 Buddhas, each mural whispering secrets of ancient rituals and the everyday hustle of Silk Road sojourners. The colors, though dulled by the sands of time, still sing in hues of ochre and lapis, each stroke a testament to a mingled palette of Indian, Chinese, Persian, and Central Asian influences.

Now, speaking about Buddhism… Buddhist tourism was one of last year’s hottest must-dos among China’s Gen Z urbanites.

The trend encouraged, and encourages, a different kind of Chinese traveler—more observant and reserved, yet eager to explore their cultural roots. It’s all about slow travel and not darting from one daka spot to the next.

The main reason behind this phenomenon is that many young urbanites want an escape from the non-stop torrents of daily life that can suck people in and not let them come up for air. The current flow and speed of China’s social environment have placed huge pressures on young shoulders, from professional to financial ones.

Xiaohongshu in June even launched its first “Slow People Festival” in Dali, southwest China’s Yunnan Province, including a series of activities such as musical performances and spiritual workshops, according to Dao Insights, a website publishing exclusive articles on and high-value case studies from the Middle Kingdom. Xiaohongshu, in doing so, aims to “help people rediscover the essence of life.”

And gazing upon the stunning natural vista, you will find that is exactly what the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves are all about: taking a Buddhist beat as people pause to embrace the depth of ancient traditions.

This author’s tour of a toasty Turpan revealed tales where bustling modernity meets tranquil wisdom of the past, allowing visitors to take a breath of fresh air. –The Daily Mail-Beijing Review news exchange item