DM Monitoring

GENEVA: As the war in Ukraine rages on, diplomats trying to salvage the languishing 2015 Iran nuclear deal have been forging ahead with negotiations despite distractions caused by the conflict. They now appear to be near the cusp of a deal that would bring the U.S. back into the accord and bring Iran back into compliance with limits on its nuclear program.

After 11 months of on-and-off talks in Vienna, U.S. officials and others say only a very small number of issues remain to be resolved. Meanwhile, Russia appears to have backed down on a threat to crater an agreement over Ukraine-related sanctions that had dampened prospects for a quick deal.

That leaves an agreement – or at least an agreement in principle – up to political leaders in Washington and Tehran.

But, as has been frequently the case, both Iran and the U.S. say those decisions must be made by the other side, leaving a resolution in limbo even as all involved say the matter is urgent and must be resolved as soon as possible.

“We are close to a possible deal, but we’re not there yet,” State Department spokesperson Ned Price said Wednesday. “We are going to find out in the near term whether we’re able to get there.”

Also Wednesday in Berlin, German Foreign Ministry spokesperson Christofer Burger said work “on drafting a final text has been completed” and ”the necessary political decisions now need to be taken in capitals.”

“We hope that these negotiations can now be swiftly completed,” he said.

Reentering the 2015 deal known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA, has been a priority for the Biden administration since it took office.

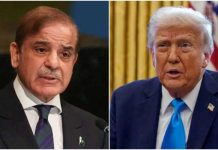

Once a signature foreign policy achievement of the Obama administration in which now-President Joe Biden served as vice president, the accord was abandoned in 2018 by then-President Donald Trump, who called it the worst deal ever negotiated and set about restoring and expanding on U.S. sanctions that had been lifted.

The Biden administration argues that any threat currently posed by Iran would be infinitely more dangerous should it obtain a nuclear weapon. Deal opponents, mostly but not entirely Republicans, say the original deal gave Iran a path to developing a nuclear bomb by removing various constraints under so-called “sunset” clauses. Those clauses meant that certain restrictions were to be gradually lifted.

Both sides’ arguments gained intensity over the weekend when Iran targeted the northern Iraqi city of Irbil with missile strikes that hit near the U.S. consulate compound. For critics, the attack was proof that Iran cannot be trusted and should not be given any sanctions relief. For the administration, it confirmed that Iran would be a greater danger if it obtains a nuke.

“What it underscores for us is the fact that Iran poses a threat to our allies, to our partners, in some cases to the United States, across a range of realms,” Price said. “The most urgent challenge we would face is a nuclear-armed Iran or an Iran that was on the very precipice of obtaining a nuclear weapon.”

Meanwhile, a new glimmer of hope for progress emerged Wednesday when Iran released two detained British citizens. The U.S., which withdrew from the nuclear deal in 2018, and the three European countries that remain parties to it had said an agreement would be difficult if not impossible to reach while those prisoners, along with several American citizens, remain jailed in Iran.

Should the prisoner issue be resolved, Price said Tuesday, the gaps in the nuclear negotiations could be closed quickly if Iran makes the political decision to return to compliance.

“We do think that we would be in a position to close those gaps, to close that remaining distance if there are decisions made in capitals, including in Tehran,” Price said.

Yet, Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amirabdolahian said a deal depends entirely on Washington.

“More than ever, (the) ball is in U.S. court to provide the responses needed for successful conclusion of the talks,” he said after meeting with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov in Moscow on Tuesday. Amirabdolahian said he had been “reassured that Russia remains on board for the final agreement in Vienna.”

Lavrov said the negotiations were in the “home stretch” and suggested that last-minute Russian objections to the potential spillover of Ukraine-related sanctions into activities Moscow might undertake with Tehran under a new nuclear deal had been overcome.

He said the agreement under consideration would carve those activities out, something the U.S. has not denied and has said the Russians should have understood from the beginning.

“We would not sanction Russian participation in nuclear projects that are part of resuming full implementation of the (deal),” Price said. “We can’t and we won’t and we have not provided assurances beyond that to Russia.”

He said the U.S. would not allow Russia to flout Ukraine-related sanctions by funneling money or other assets through Iran. Any deal “is not going to be an escape hatch for the Russian Federation and the sanctions that have been imposed on it because of the war in Ukraine.”

Deal critics are skeptical that Russia won’t at least try to evade Ukraine sanctions in dealings with Iran and have warned that potential sanctions-busting is just one reason they will oppose a new agreement.

Earlier this week, all but one of the 50 Republicans in the Senate signed a joint statement vowing to dismantle any agreement with Iran that has time limits on restrictions to advanced nuclear work, or that does not address other issues they have, including Iran’s ballistic missile program and military support for proxies in Syria, Lebanon and Yemen.

While the GOP won’t be able to stop a deal now, it may have majorities in both houses of Congress after November’s midterm elections. That would make it difficult for the administration to stay in any deal that is reached.

Another concern of deal critics is the scope of sanctions relief that the Biden administration is ready to provide Iran if it comes back into compliance with the deal. Iran has been demanding the removal of the Trump administration’s designation of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) as a “foreign terrorist organization.”

The U.S. has balked at that, barring Iranian commitments to stop funding and arming extremist groups in the region and beyond. The matter is of considerable interest in Washington, not least because the IRGC is believed to be behind specific and credible threats to former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and the Trump administration’s Iran envoy Brian Hook.